Guide to Prenatal Genetic Testing and Screening

Prenatal screening and diagnostic testing can provide expectant parents with critical information about the health of their unborn baby—from treatable health conditions to birth defects and genetic disorders. While optional prenatal tests are available to all pregnant people, they are not always the best choice for everyone. The results of genetic tests have the potential to bring either a sense of relief or additional anxiety to a pregnancy.

“Regardless of how healthy you or your family are, there’s always a background risk of about 3% to 5% that your baby could be born with a birth defect or genetic condition,” said Blair Stevens, MS, CGC, prenatal expert for the National Society of Genetic Counselors. “Most genetic tests provide reassurance because most babies are born perfectly healthy. And so, if reassurance is something that you would feel would be helpful, then that—most of the time—is what you’ll end up getting.”

This guide houses information about different types of prenatal genetic tests, genetic conditions that can be diagnosed before birth, how and when certain tests are performed and considerations for undergoing prenatal genetic testing.

Table of Contents:

What Is Prenatal Genetic Testing?

Throughout gestation, pregnant people undergo routine testing and screening to monitor their health and the health of their baby. Regular checkups throughout pregnancy provided to all patients include:

- Blood pressure checks to monitor for preeclampsia, which can occur during the second half of gestation.

- Urine tests to check for infections, preeclampsia and other conditions.

- Blood tests to check for infections, blood type, anemia and other factors.

- Weight monitoring to ensure the parent and child are gaining an appropriate amount of weight.

There are also a variety of optional genetic screening and diagnostic tests that can help determine whether an unborn baby has a genetic disorder or birth defect. Prenatal screenings estimate the chances that a baby will be born with a genetic disorder, while diagnostic tests indicate if the fetus actually has a condition. Depending on the results of screenings, individuals and providers may pursue additional diagnostic testing to get a clearer picture of a baby’s health.

“A screening test would never tell you 100 percent something is present or zero percent something is not present,” said Dr. Nicholas Behrendt, a maternal-fetal medicine specialist with Colorado Children’s Hospital.

Types of Prenatal Screenings and Tests for Genetic Disorders

Carrier screenings can be done on parents before pregnancy to determine if they carry a gene for inherited disorders.

Preimplantation genetic diagnosis is used for patients undergoing in vitro fertilization (IVF). The embryo is tested for genetic disorders and mutations before it is transferred to the uterus.

Prenatal genetic screening tests estimate the chance that a fetus has a genetic disorder but are not meant to say with certainty that the condition is actually present.

Prenatal diagnostic tests show whether a fetus actually has a genetic disorder after a screening test indicates a risk.

Sources:

- Prenatal Genetic Diagnostic Tests: Frequently Asked Questions. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

- Prenatal Genetic Screening Tests, Frequently Asked Questions. American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Retrieved February 23, 2022.

“The goal is to detect these genetic conditions that families might want some information on,” said Hannah Elfman, MS, CGC, a genetic counselor with University of Colorado Medicine and Children’s Hospital Colorado.

Screenings only indicate the possibility of a genetic condition, rather than total assurance. If a screening has a positive result, individuals can then have conversations with their health providers and genetic counselors about the accuracy of the screening test, along with next steps for confirming or ruling out a diagnosis.

“Our ability to screen for differences in genetics and differences in structural development has come a long way over a pretty short time period, but we’re always improving,” Behrendt said.

Some tests, such as carrier screenings, can be done before pregnancy to understand whether an individual carries a gene for a genetic disorder that a future child may inherit. Elfman recommended testing before starting a family, as well as having conversations with family members to learn if any relatives have had genetic disorders.

“I find a lot of people don’t share that information or don’t ask beforehand, and that might shift some conversations,” Elfman said.

Some of the conditions that care providers use prenatal screenings and tests to look for are listed below.

Glossary: Genetic Disorders That Can Be Diagnosed Before Birth

Aneuploidy (pronounced “an-yuh-ploy-dee”)

One or more missing or extra chromosomes.

Cystic fibrosis (pronounced “si-stik fai-bro-sis”)

Progressive genetic disorder that affects the lungs, pancreas and other organs; causes lasting lung infections; and limits the ability to breathe over time.

Down syndrome (pronounced “down sin-drohm”)

Condition in which a person has an extra copy of chromosome 21—and the most common chromosomal abnormality diagnosed in the United States—that causes mental and physical developmental challenges. There are three types: trisomy 21 (the most common), Translocation Down syndrome and Mosaic Down syndrome.

Duchenne muscular dystrophy (pronounced “doo-shen muh-skyoo-lar dis-truh-fee”)

Genetic disorder characterized by progressive muscle weakness and degeneration caused by alterations to dystrophin, a protein that keeps muscle cells intact.

Hemophilia A (pronounced “hee-mow-fee-lee-yuh ay”)

Hereditary bleeding disorder in which blood cannot clot properly.

Polycystic kidney disease (pronounced “pah-lee-sis-stik kid-nee deh-zeez”)

Genetic disorder and type of chronic kidney disease that causes fluid-filled cysts to grow on the kidneys.

Sickle cell disease (pronounced “sik-uhl sehl deh-zeez”)

A group of hereditary blood disorders that causes red blood cells to become hard and C-shaped rather than round, causing them to die early and clog blood flow.

Spina bifida (pronounced “spy-nuh bih-fih-duh”)

Neural tube defect in which the spine and spinal cord do not form or close properly during gestation.

Spinal muscular atrophy (pronounced “spy-nuhl muh-skyoo-lar ah-truh-fee”)

Genetic motor neuron disease that affects the central nervous system, peripheral nervous system and voluntary muscle movement.

Tay-Sachs disease (pronounced “tay-saks deh-zeez”)

Genetic disorder in which the person lacks an enzyme to help break down fatty substances (gangliosides), which build up in the brain and spinal cord and affect nerve function.

Thalassemia (pronounced “tha-luh-see-mee-yuh”)

Genetic blood disorder in which the body does not make enough hemoglobin, a protein in red blood cells, leading to anemia and fewer healthy red blood cells in the bloodstream.

Trisomy 13/Patau syndrome (pronounced “try-suh-mee thehr-teen” or “pah-tow sin-drohm”)

A type of aneuploidy and chromosomal condition that can cause intellectual disabilities and physical abnormalities, including heart defects, brain or spinal cord abnormalities, small eyes, extra fingers or toes, a cleft lip and/or cleft palate and weak muscle tone.

Trisomy 18/Edwards syndrome (pronounced “try-suh-mee ay-teen” or “ed-wahrds sin-drohm”)

A type of aneuploidy and chromosomal condition that can cause individuals to have low birth weight and physical abnormalities such as heart defects, small/abnormally shaped heads, small jaws and mouths or clenched fists with overlapping fingers.

Who Should Get Prenatal Genetic Testing?

While prenatal genetic screening and testing are available to all pregnant people, these tests are not suitable for everyone.

Some individuals have heightened risk factors for carrying a child with a genetic disorder, so screening and testing may be recommended for high-risk pregnancies. These include pregnancies in which:

- The pregnant person is 35 years old or older.

- The pregnant person previously gave birth to a premature baby or a baby with a birth defect.

- The pregnant person is carrying more than one child.

- Either parent has preexisting conditions.

- Either parent comes from an ethnic background in which certain disorders are more common.

Stevens, who also serves as a prenatal genetic counselor with McGovern Medical School at The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston and UT Physicians, said it is important for expectant parents to consider how they would handle knowing more about their child’s health: Would having more information be empowering—regardless of the results—or would it create additional anxiety?

“Risk factors aside, I think it’s really more personality and coping style,” Stevens said. “Anyone, I think, could benefit from prenatal screening, but it’s not right for everyone.”

Some pregnant people may choose to terminate a pregnancy based on the results of a prenatal genetic test. However, having information early can help providers intervene sooner and improve a baby’s outcome in some cases if a child is diagnosed with a genetic condition. For example, for an unborn baby diagnosed with spina bifida, the defect can be repaired in utero rather than after birth. Other diagnoses have less actionable implications, but knowing about them ahead of birth may help individuals prepare for what to expect—even if that means preparing for the death of their child or planning for long-term specialty care.

“The more they can adjust prenatally, the more they are ready to welcome their baby with open arms and less fear and more joy,” Stevens said. “It just depends what the diagnosis is. How severe is it? How certain are we on the prognosis?”

Questions Expectant Parents Can Ask About Prenatal Screening and Testing

The questions below may guide decision-making around genetic screening and testing.

Questions to Ask Yourself

- How much do I want to know?

- How does information affect me? Am I an information seeker who desires information even if it comes with uncertainty? Or am I more of an information avoider, and too much information leads to anxiety and feeling overwhelmed?

- Knowing that most healthcare providers prefer having more information, am I someone who wants to do whatever my provider tells me to do?

- How would I use the results of a prenatal screening or diagnostic test? Would I make different decisions about my pregnancy based on the results?

- How would I handle it if my baby tests positive for a genetic disorder?

- If I learned my baby had a genetic disorder, would knowledge of that condition be valuable earlier in the pregnancy?

- How will the information I gain from testing shape my prenatal care?

- How will testing information affect my planning for early childhood care?

Questions to Ask Your Provider

- What factors put my baby at risk for certain genetic conditions?

- How are certain tests performed?

- What are the risks of particular tests to me and to the baby?

- How accurate is the screening or diagnostic test?

- If I elect to have a screening or test done, how can I prepare for my appointment?

- How long does it take to receive prenatal genetic testing results?

- What support is available after I receive results? Will you refer me to a genetic counselor, social worker and/or mental health professional to discuss the results?

- If I have questions or need more information after a test, who is the expert I can consult? Is my obstetrician or nurse well versed in genetic testing and outcomes, or is there another expert who can help me?

How Is Prenatal Testing Done?

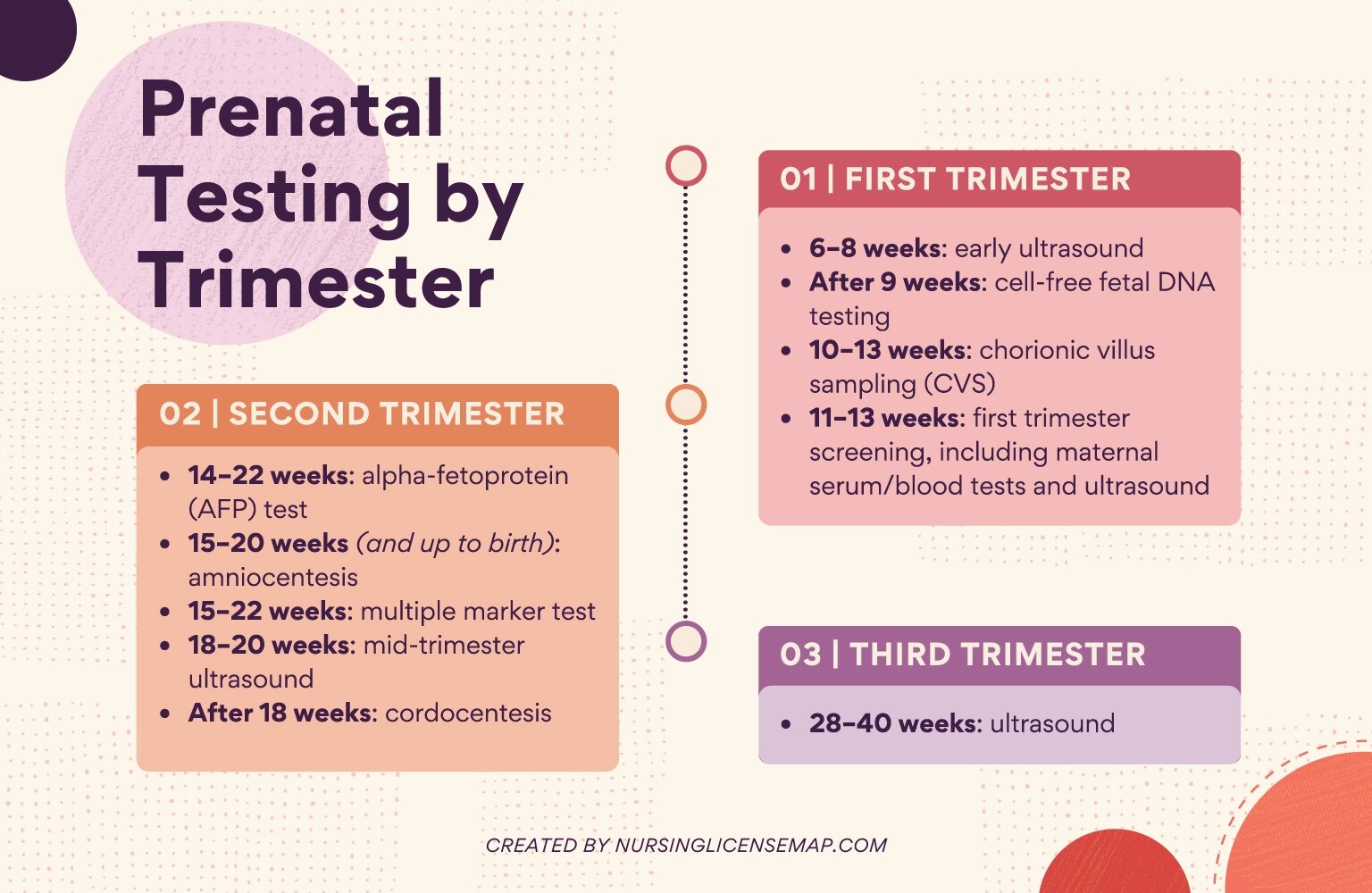

Learn more about the different types of prenatal testing procedures below, including if they are diagnostic or screening tests, how prenatal tests are performed, when they occur and whether the tests are part of routine prenatal checkups.

Types of Prenatal Screenings and Tests

Alpha-fetoprotein (AFP) screening

This blood test measures the level of alpha-fetoprotein (AFP), a protein produced by the fetus, in the pregnant person’s blood during pregnancy. The screening is part of routine pregnancy care, and there are no known risks to the pregnant person or fetus, aside from mild pain or bruising at the site of the needle. AFP levels fluctuate throughout pregnancy; however, abnormal levels of AFP may indicate defects in the fetal abdominal wall, Down syndrome or other chromosomal abnormalities, neural tube defects, or twins or multiple births. Additional diagnostic testing may be required to determine if the fetus(es) has any genetic conditions.

This diagnostic test uses a thin, hollow needle to draw amniotic fluid, which is tested to indicate whether an unborn baby has a birth defect or genetic disorder, such as cystic fibrosis, Tay-Sachs disease, chromosomal disorders such as Down syndrome, or neural tube defects. This procedure is optional and carries a small (less than 1%) risk of miscarriage.

Cell-free fetal DNA screening or non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT)

This optional screening test is among the most common procedures used to screen for genetic conditions and tests the pregnant person’s blood for the baby’s DNA to determine if the baby may have chromosomal abnormalities like Down syndrome, trisomy 13 or trisomy 18. The screening poses little risk to the pregnant person or baby, aside from mild pain or bruising at the site where blood was drawn. However, additional diagnostic testing may be required to determine if the baby has any genetic conditions.

Chorionic villus sampling (CVS)

This optional diagnostic test uses a tissue sample from the placenta to diagnose genetic conditions including Down syndrome, cystic fibrosis, sickle cell disease and Tay-Sachs disease. There are two types of CVS tests: Transabdominal tests use a long, thin needle to take a sample through the pregnant person’s abdomen, while transcervical tests use a thin tube to take a sample through the cervix. Risks of the procedure include miscarriage (about 1%), infection, bleeding and transverse limb defects in the baby (about 0.03%).

Multiple marker test: Triple marker screening or quad marker screening

These optional blood tests check the levels of proteins and hormones in the pregnant person’s blood. Both the triple marker and quad marker screenings check for AFP, human chorionic gonadotropin (HCG) and unconjugated estriol, and the quad marker screening also tests levels of inhibin-A, a protein produced by the placenta and ovaries. Abnormal levels of these substances may indicate a risk for chromosomal disorders or neural tube defects. Additional diagnostic testing is required to determine if a baby actually has any genetic conditions.

Percutaneous umbilical blood sampling (cordocentesis)

This optional diagnostic test uses a thin, hollow needle to take a sample of the baby’s blood from the umbilical cord to diagnose genetic disorders, anemia and infections. Cordocentesis is typically only used when a diagnosis cannot be made through other methods because of risks including fetal bleeding, blot clotting, lowering the baby’s heart rate, infection and loss of pregnancy.

Ultrasounds are given routinely throughout pregnancy and can be used for screening and diagnosis. Sound waves create images that provide information about a fetus’s health. While ultrasounds are part of routine checkups to monitor a baby’s development, they can also help check for indications of birth defects, Down syndrome and other chromosomal abnormalities. Ultrasounds are considered safe during pregnancy, and 2D, 3D or 4D options are available.

Additional Resources on Prenatal Genetic Testing

Support groups can be helpful for families of children with genetic disorders, Behrendt said. He encourages families who receive a prenatal genetic diagnosis to meet others who have had a similar experience.

“We can even attempt to have them meet up with a family that has gone through a similar process,” Behrendt said. “Our goal, after you’ve seen us—during the pregnancy but probably more importantly when you leave the hospital with your baby—is [to identify] the plan from there. How do we give you support? How do we give your child support?”

The resources below offer additional information about genetic screening, testing and counseling for people considering starting a family, expectant parents and their loved ones.

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: How to Cope When Your Unborn Baby Is Diagnosed With a Birth Defect

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia: How to Support a Mother Who Receives a Prenatal Diagnosis During Pregnancy

- Genetic Support Foundation: Pregnancy and Genetics

- Johns Hopkins Medicine: Preventing and Treating Birth Defects: What You Need to Know

- Lettercase: Digital and Print Resources for Genetic Conditions

- National Library of Medicine: What Are the Risks and Limitations of Genetic Testing?

- National Organization for Rare Disorders: For Patients and Families

- National Society of Genetic Counselors: Find a Genetic Counselor

- Seattle Children’s: How to Handle a Difficult Prenatal Diagnosis

And the following organizations offer more information about specific conditions and support for those affected by them:

Cystic fibrosis

Down syndrome

Duchenne muscular dystrophy

Hemophilia A

Polycystic kidney disease (PKD)

Sickle cell disease

Spina bifida

Spinal muscular atrophy

Tay-Sachs Disease

Thalassemia

Trisomy 13 and 18

Please note that this article is for informational purposes only. Individuals should consult their health care provider before following any of the information provided.Post navigation

< How Nurses Can Support Children With Autism During Medical Visits