How to Talk to Teens About Performance-Enhancing Substances

American Assembly for Men in Nursing member Rasheem Wynn, BSN, RN, remembers traveling to basketball games with his daughter, then a nationally ranked high school player, and observing her world up close. Wynn would notice the other players’ habits, particularly the unhealthy behaviors.

“You’re sitting on the sidelines, and you see nothing but the Monsters (energy drinks) and all that stuff,” he said.

Wynn would point them out to his daughter, an aspiring college athlete, saying “I guarantee you by game four she’s going to be cramping, she’s going to be dehydrated, and next thing you know, she’ll be out of the game.”

Together they would track the player throughout the tournament.

“Sure enough, we would see that time and time again,” he said. Another athlete seemingly at peak performance would be out of the game far sooner than expected.

The pressure to perform affects many adolescents, not just athletes—and performance-enhancing substances (PES) can seem like an easy solution. Students buckling under academic pressure might use stimulants to stay awake and study longer. Teens who are highly engaged on social media may use supplements to build muscle or to lose weight. But using these substances can have unintended consequences for adolescents. These effects range from benign, such as wasted money on ineffective supplements, to devastating, such as heart problems.

“They have so much pressure to stay on top, to be better than everyone else,” said Wynn. “Sometimes that choice can be fatal for these kids.”

Families, coaching teams, educators and health providers need to understand the risks of PES and know the alternatives so they can all support teenagers in making healthy decisions that support their long-term performance goals.

What Are Performance-Enhancing Substances?

As a category, PES encompasses both illicit performance-enhancing drugs and legal, over-the-counter products.

Performance-enhancing drugs include anabolic steroids (e.g., testosterone), designer steroids, human growth hormone (hGH) and others. According to the Mayo Clinic, these drugs can have serious health risks, and using them in sports (referred to as “doping”) is banned. Another example are amphetamines, which are prescribed to treat ADHD and may be illegally used as stimulants.

Other forms of performance enhancers are typically available over the counter, including:

- Creatine

- Protein supplements (e.g., powders, shakes, bars)

- Non-prescription diet pills

- Caffeine and other stimulants

- Multivitamins

- Energy drinks

Protein supplements, stimulants and creatine are most commonly used among adolescents, according to Pediatrics’ most recent clinical report on PES usage.

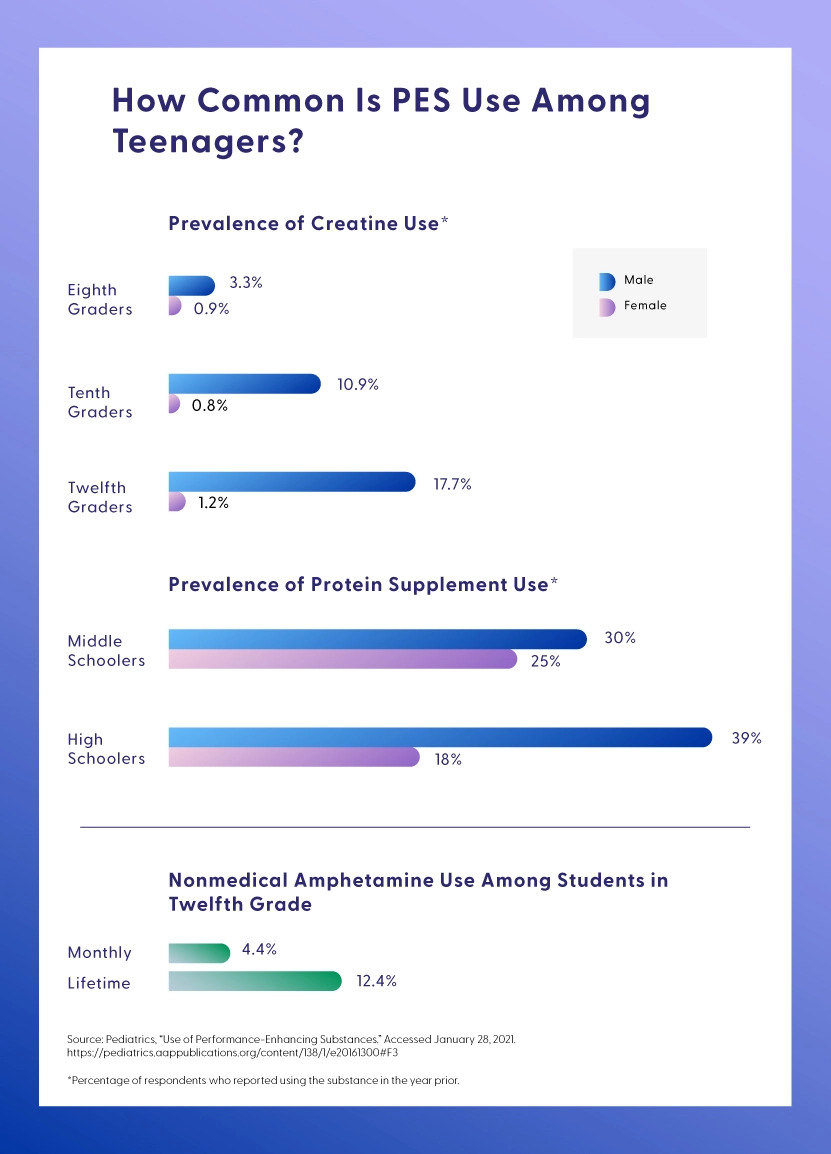

The older the age group, the greater the prevalence of creatine use for adolescent boys and girls in eighth, tenth, and twelfth grades. Prevalence was greater for boys than girls at every grade level. About 3.3% of boys and 0.9% of girls in eighth grade reported using creatine in the past year, compared to 17.7% of boys and 1.2% of girls in grade 12. Around 30% of middle school boys and 39% of high school boys reported using protein supplements during the past year. Prevalence of protein supplement use was lower for high school girls (18%) than middle school girls (25%). Among students in 12th grade, 12.4% had ever used nonmedical amphetamines; about 4.4% used them monthly.

Read a full transcript of the infographic How Common Is PES Use Among Teenagers?

Why Do Adolescents Use Performance Enhancers?

As the name suggests, children and adolescents use PES to improve their performance, often for sports. Latonya Law, DNP, believes that, for teenage athletes, the appeal has to do with media influence and the pressure to perform at a collegiate level.

“They see a lot of people going to the NBA and NFL, and they’re thinking that if they use this substance, it will build them up to be able to work harder and perform better,” she said.

Other adolescents use PES such as supplements to “enhance” their appearance, according to the Pediatrics report. Some want to increase their muscle tone or definition, apart from any organized athletic activity, while others want to lose weight, as the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health supplement guidance points out. Still other teens use stimulants, a form of PES, to help them better focus on schoolwork, according to TeensHealth’s page on “study drugs.”

Whatever teenagers’ reasons for using substances researchers have noticed some patterns among them. In various studies of adolescents, PES use has been positively correlated with body dissatisfaction, higher body mass index (BMI), training in a commercial gym and exposure to appearance-oriented media, especially about building muscles.

FAQ: What Parents Need to Know About Performance-Enhancing Substances

PES, PARTICULARLY PROTEIN SUPPLEMENTS, ARE OFTEN UNNECESSARY.

For many teenage athletes, consuming extra protein is excessive, according to Children’s Hospital of Orange County (CHOC) safety guidance on protein powders. Most get enough from their daily nutrition. (However, CHOC noted that some children may benefit from supplements, including those who are vegan or vegetarian, underweight or have certain medical conditions. Parents should discuss supplementing with their child’s health provider before making any changes to their nutrition.)

“Studies show that consuming extra protein will produce no further gain in strength, muscle mass or size,” wrote pediatric hospitalist Jacqueline Winklemann.

PES ARE OFTEN INEFFECTIVE AND CAN EVEN BE DANGEROUS.

In a 2019 retrospective Journal of Adolescent Health study on dietary supplements’ effects on children, adolescents and young adults, researchers found that, of the 977 “single-supplement-related adverse events” reported to the FDA between 2004 and 2015, about 40% led to a severe medical event such as hospitalization, disability or death. Supplements marketed for muscle building, weight loss and energy had three times the risk of a severe event than vitamins.

In particular, consuming too much protein can be toxic for teenagers, even teenage athletes, causing nausea, lack of appetite, diarrhea and stress on the liver and kidneys. Research has demonstrated that high-protein diets, though popular for weight loss, can worsen renal functioning in those with kidney problems—and possibly those without, according to a Journal of the American Society of Nephrology study in 2020.

Even in moderation, protein and other performance enhancers tend to be ineffective in the long run, according to nurses.

“They might perform well for a little bit, but their endurance doesn’t last as long,” said Law. “When you see [athletes] tiring out quickly, I think it almost makes them feel like they are not doing well unless they go back and drink another shake.”

Rasheem Wynn agreed that PES may offer a temporary boost. “But the long-term physical effects truly affect people’s bodies,” he said. The Mayo Clinic’s description of performance-enhancers indicates that side effects can include:

- Testosterone issues

- Stroke

- Irregular heartbeats

- Insomnia

- Anxiety

- Stomach problems

- High blood pressure

- Stress of the kidneys and liver

PES ARE UNREGULATED AND MAY BE HARMFUL FOR ADOLESCENTS.

Parents and coaches should also note that dietary supplements are regulated “in a post-market fashion,” according to the U.S. Anti-Doping Agency’s Supplement 411 resource. The Food and Drug Administration (FDA) does not approve supplements for safety and label accuracy prior to sale. They are only taken off the market after causing harmful side effects or death, wrote registered and licensed dietitian Erin Coleman in an SFGATE article on protein supplements.

The lack of regulation also means that protein supplements could include harmful ingredients such as steroids, which could lead to heart, liver and kidney issues.

Caffeine can cause problems as well. For adolescents, consuming too much has been associated with nervousness, irritability, nausea, cardiovascular symptoms, difficulty sleeping, osteoporosis and gastric ulcers, according to a 2018 summary on caffeine and children.

A Michigan Medicine article on the dangers of caffeine reported that excessive intake can cause cardiac or neurological toxicity (damage to the heart or nervous systems, respectively), which could require hospitalization. In rare cases, it could lead to death.

USING PES AS AN ADOLESCENT CAN BE A GATEWAY TO LATER SUBSTANCE USE.

In a 2020 Pediatrics study on legal performance-enhancing substances, researchers found that PES use in adolescence and young adulthood was associated with problematic alcohol use and other risky behaviors later on.

As with any substance, performance enhancers themselves can be misused or abused. Behaviors can subtly become habits that could harden into addiction, said Joseph Melendez, LICSW, a clinician with experience in substance use treatment.

Melendez encourages parents to watch for subtle flags that their teens’ use could become problematic: requesting more kinds of substances (e.g., multivitamins on top of caffeine pills and protein shakes) or a greater amount. For example, if the child uses up in one week a canister of powder that used to last one month, there may be cause for concern.

How to Talk About PES and Performance Pressure With Adolescents

For many adolescents, especially teenage athletes, PES use is connected to an intense pressure to perform and succeed. Many factors contribute to this dynamic, including family expectations, cultural backgrounds, athletics, academics and the uncertainty of life after high school.

Parents, health care providers, educators and coaches can each play a role in helping kids learn to cope with pressure in healthy ways.

Parents and Families

UNDERSTAND HOW YOUR OWN EXPECTATIONS MAY BE DRIVING YOUR CHILD TO PERFORM.

“We have a tendency to live our lives through our children, especially in sports, and I think sometimes that’s a lot of the pressure,” said Wynn. Parents should try to create some space between their own hopes and their children’s and be vocal about supporting whatever path the child chooses. Wynn suggests saying, “I’m here to help you make that decision, but I’m not going to force my dreams on you.”

ASK WHY THEY STARTED USING A PERFORMANCE ENHANCER.

Were they inspired by a YouTube video or encouraged by a coach? Understanding the underlying desire can help parents understand why their child wants to try a performance enhancer and how best to support them, said Melendez.

School Nurse and Primary Care Providers

START THE CONVERSATION ABOUT PES.

In her clinical practice, Law notices that many adolescents are actually open to discussing PES because they often do not view it as a problem. “I try to educate them and motivate them to let them know they can do this on their own without anything added,” she said.

PROVIDE EDUCATION ABOUT HEALTHIER WAYS TO IMPROVE PERFORMANCE, SUCH AS CREATINE ALTERNATIVES.

Law encourages patients to focus on consistent healthy actions, including fluids and good nutrition, and regular training for teenage athletes. “It’s a daily living type of thing instead of just for that moment,” she said. “That’s where I definitely see the performance powders being used because they want a quick fix.”

TAKE NOTE OF PERSONALITY CHANGES AND EVASIVE BEHAVIORS.

Students using performance-enhancing drugs may become more irritable, aggressive or anxious, according to a National Institute on Drug Abuse research report on these drugs. Some may use diuretics to flush any trace of drugs from their system, as reported by the BBC on sporting ethics. Watch for these potential indicators and stay in touch with the student’s support system, including their health team.

Educators

ALWAYS INVOLVE THE PARENTS IF YOU NOTICE A PROBLEM.

Depending on the relationship, educators may be able to discuss concerns about PES use with the student directly, said Melendez. Regardless, they should involve the parents and report any warning signs. If parents will not listen, Melendez encourages teachers to lean on the school’s resources, such as a school counselor or social worker.

HELP STUDENTS BEGIN TO THINK ABOUT LIFE OUTSIDE OF HIGH SCHOOL.

The pressure to succeed in sports, academics and social life can be intense for adolescents in a performance-driven culture. “That’s rewarded in our society, [with] big contracts and TV shows, but they don’t show what happens when the lights burn out and the field is empty,” said Wynn. Educators are well positioned to help students see past a college acceptance or recruitment, which may relieve some pressure.

Coaches and Athletic Trainers

DEVELOP SMART GOALS WITH TEENAGE ATHLETES.

Instead of giving vague directives such as “bulk up,” work with student-athletes to create specific goals to improve their performance gradually but sustainably. “SMART” goals are specific, measurable, achievable, realistic and timely.

ENCOURAGE PLAYERS TO TRAIN REGULARLY, EVEN IN THE OFFSEASON.

Law said that she sees PES use increase around the time that sports seasons start because players are trying to quickly regain ground. “But if you educate them and tell them to train on a regular basis, it seems to help them play better,” she said.

Alternatives to Creatine and Other Performance-Enhancing Substances

Teenagers trying to improve performance on the field or in the classroom do not need to resort to PES, and those aiming to “enhance” their appearance can find safer methods than a bulking workout and “healthy” protein powders. However, they may need help finding better ways of achieving their goals. Find several options and resources for support below.

Protein From Food: Teenage athletes need only slightly more protein than non-athlete peers. The Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics indicates the current daily protein recommendation is 46 grams for teenage girls and 52 grams for teenage boys.

Nutrition: Whole foods rich in micronutrients can be more effective than supplements, says registered and licensed dietitian Natalie Butler. Try raw sprouts (e.g., radish and broccoli), flax seeds, beet juice or Brazil nuts.

Hydration: Girls ages 14 to 18 should have 10 cups of water per day, while boys in the same age range should have 14 cups, according to the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics guidance on kids’ water consumption.

Working With a Trainer: An athletic trainer can guide teenagers in becoming more fit in a balanced, healthy way so they do not turn to substances.

Support From Health Professionals: For adolescents struggling with body image or other performance pressures, getting support from a school counselor, therapist or nutritionist can provide some guidance and relief.

Rest: Rest is critical for building muscles and for general well-being. According to CHOC, strength training for a particular body part should be done on non-consecutive days, and adolescents should get eight or nine hours of sleep each night. A recent survey suggested that consistent sleep can even lead to better grades: Students surveyed who got 8.1 hours a night earned mostly As, while those with 7.6 and 7.3 earned mostly Bs and mostly Cs, respectively.

Performance-enhancing substances can be attractive to adolescents. They provide a seemingly simple solution that circumvents disciplined study, careful training and intentional recovery.

“But this is not the way that you actually improve your performance,” said Law. Hydration, nutrition, rest and professional support can lead to healthy, sustainable gains.

“That’s a lesson that you can use for the rest of your life,” said Law.

Resources to Learn More About Teens’ Health

Behavioral Health Treatment Services Locator | Substance Abuse and Mental Health Services Administration: directory of treatment facilities for mental health and substance use issues, searchable by address, city and zip code.

Emotional Health | Center for Young Women’s Health: guides written for girls and young women on mental health topics including self-harm, gender identity, eating disorders and depression.

Emotional Health | Center for Young Men’s Health: guides written for boys and young men on mental health topics including counseling and therapy, sexual consent, school violence and meditation.

Go Ask Alice! | Columbia University: forum for users to confidentially submit health questions to Columbia University’s team of health professionals.

Guided Meditations | Mindfulness for Teens: downloaded recordings of guided meditations for teenagers, ranging from three minutes to half an hour.

Health Guides | Center for Young Women’s Health: collection of guides on physical and mental health for girls and young women with topics ranging from stretching to friendship to pelvic exams.

Health Guides | Center for Young Men’s Health: collection of guides on physical and mental health for boys and young men with topics ranging from birth control to chronic illness to healthy relationships.

Mental Health Resource Center | The Jed Foundation: crisis line for adolescents to text and call and information on emotional issues that commonly affect them.

Mind | TeensHealth: compendium of resources for teens on relationships, body image, families and emotions.

Nutrition Guide: Fueling for Performance | USADA (PDF, 1.9MB): guidelines for athletes to fuel and hydrate their bodies well for competition.

TMH Speaks … Mags | TeenMentalHealth.org: series of six online magazines with explanations of common mental health disorders, coping strategies and where to find support.

Tools and Apps | ReachOut.com: quiz that helps users find professionally reviewed online tools that support their health and well-being.

Please note that this article is for informational purposes only. Individuals should consult their health care provider before following any of the information provided.

The following section includes real text from the graphic in the post.

Annual Creatine Use

| School Grade | Males (%) | Females (%) |

|---|---|---|

Grade 8 | 3.3 | 0.9 |

Grade 10 | 10.9 | 0.8 |

Grade 12 | 17.7 | 1.2 |

Protein Supplement Use

| School Age | Girls (%) | Boys (%) |

|---|---|---|

Middle School | 25 | 30 |

High School | 18 | 39 |

Nonmedical Amphetamine Use Among Students in Grade 12

| Frequency | Total (%) |

|---|---|

Monthly | 4.4 |

Lifetime | 12.4 |

< Everything You Need to Know About Artificial Intelligence and Your Patient Data